In Laredo, families grapple with air pollution as efforts to reduce toxic emissions stall

Nidia Nevares walks with her son, Juan Jose "JJ" Nevares, at Father Charles M. McNaboe Park on Sept. 20, 2025. The park is near both their home and the Midwest Sterilization Co. plant, which uses a known carcinogen. Photo by Sean Jimenez/South Texas Project

Activists and residents organize As ThEy fear their city might be a hotspot of exposure to a dangerous chemical.

Editor’s note: A version of this story first appeared in the South Texas Project at Texas A&M University's Department of Communication and Journalism, which also facilitated the field reporting.

Haga clic aquí para leer este reportaje en español.

LAREDO, Texas – The Nevares family home is a lively space, with kittens milling about and happiness in the air. It’s a feeling the family had to fight for, following a devastating leukemia diagnosis for their youngest son seven years ago.

Not far from them lives Xavier Ortiz, a hardworking man who wants to provide for his family but is hindered by an aggressive cancer.

Both families live near the Midwest Sterilization Corporation, a medical equipment sterilization facility in north Laredo that uses in its process ethylene oxide, a known carcinogen.

For the Nevares and the Ortiz families, their cancer battles took on a different light once they learned about that nearby plant. They wonder if the illnesses that turned their lives upside down were caused by cancer-causing emissions from the factory and worry about how air contamination may harm others.

The Midwest Sterilization Corporation facility in Laredo uses ethylene oxide, a carcinogen, to sterilize medical equipment. The process is known to emit cancer-causing gas into the air. Photo by Sean Jimenez/South Texas Project

Local activists have been bringing attention to ethylene oxide emissions for years, advocating for more air monitoring and emission regulations. In March 2024, they applauded the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for what seemed like a victory: new federal regulations that would drastically curb emissions of ethylene oxide, including those at the facility in Laredo.

But the EPA’s 2024 “final rule” may not be the last word, as the Trump administration has been reconsidering many Biden-era regulations, placing the implementation of emissions reductions in uncertainty.

The Midwest Sterilization Corporation uses ethylene oxide to sterilize medical devices. Some families living near the plant say they understand the purpose of the facility, but struggle to see how it justifies the potential health risks.

“The products that they have, yes, they saved my son's life, because they are products for hospitals,” said Nidia Nevares, whose son survived from leukemia. But pollutants from the same plant may have made him sick in the first place, she added.

Rafael and Nidia Nevares, with their son Juan Jose "JJ”, at Father Charles M. McNaboe Park in Laredo, Texas. Photo by Sean Jimenez/South Texas Project

Old battle in a new light

Thirteen year-old Juan Jose Nevares, who goes by JJ, was diagnosed with acute lymphocytic leukemia in 2018, when he was just six. He beat the disease, but his family still lives just a few miles from the Midwest plant.

His mom, Nidia Nevares, remembers the original checkup as a “minor nuisance,” having to travel to San Antonio for tests to be done and news to get back.

The “nuisance” trip turned into a life-changing experience once the cancer diagnosis came back.

“At first, they said it was two years of treatment,” she said. “Two years passed, but after two years they told us the leukemia came back, so it was another three years of treatment.”

Nidia Nevares holds her son JJ's hand at their home, which is one of many residences located just minutes away from a controversial facility for using a carcinogen to sterilize medical equipment. Photo by Sean Jimenez/South Texas Project

“I didn’t really understand anything,” JJ recalls of his years battling cancer. “I didn’t really have adult feelings yet, so I didn’t really just know. I just said, okay, we’re doing this now.”

The Nevares family rallied around JJ and his treatment. It wasn’t until later that they learned about the potential ethylene oxide exposure from the nearby Midwest Sterilization plant and that the chemical raises the risk of cancers such as leukemia.

It was an “ugly” feeling to consider that her son’s cancer may have been linked to the toxic emissions, Nidia Nevares said. The school is close to the plant, too. She thinks about the other children that go to JJ’s school and feels “sad that more children are at risk.”

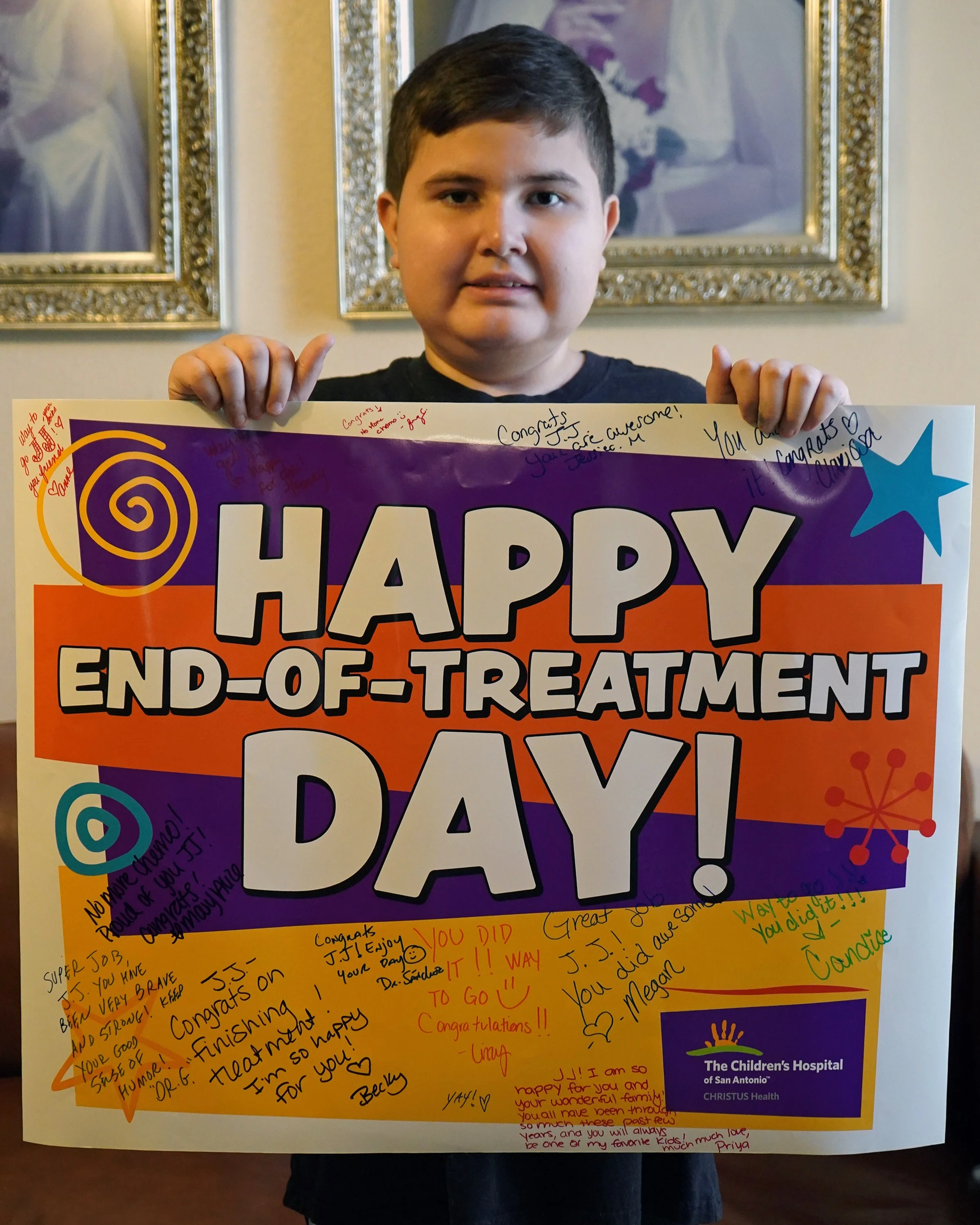

Juan Jose “J.J.” Nevares holds his end-of-treatment day poster from The Children's Hospital of San Antonio at his home in Laredo. Photo by Sean Jimenez/South Texas Project

Fighting toxins

The effort to study ethylene oxide emissions in Laredo was an all-hands-on-deck mission that began several years ago under the Clean Air Coalition in Laredo, which brought together activist groups, elected officials and school districts.

“Everybody is learning [about ethylene oxide] to advocate to the community and, at the same time, advocate it to city council and to the people that can actually make changes,” said Edgar Villaseñor, advocacy campaign manager at the environmental justice group Rio Grande International Study Center (RGISC).

Edgar Villaseñor, advocacy campaign manager at the environmental justice group Rio Grande International Study Center (RGISC). Photo by Sean Jimenez/South Texas Project

Ethylene oxide is a flammable, colorless gas used to sterilize medical equipment. It is also a carcinogen. According to the National Cancer Institute, “the ability of ethylene oxide to damage DNA makes it an effective sterilizing agent, but also accounts for its cancer-causing activity.”

For many medical devices, sterilization with ethylene oxide is a method that has proved to ensure sterility without damaging the device.

Following a 2022 investigative report published by ProPublica and The Texas Tribune, many residents became aware for the first time that Laredo is one of the cities with the highest levels of excess cancer risk.

Upon learning of the contamination risk from ethylene oxide, Laredo city officials funded a fenceline monitoring study administered by RGISC. The center hired Richard Peilter, an air quality scientist at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, to consult on the air quality within the community.

“Particularly elevated concentrations were consistently observed in areas proximate to the facility, indicating a localized source of emission,” according to the 2024 report, referring to the Midwest Sterilization plant.

The report states there are some concerns with the reliability of the data, to which it recommends ongoing monitoring. “[Ethylene oxide] exposure poses an important risk to communities and should not be dismissed,” it says.

Edgar Villaseñor explains the varying levels of air contamination affecting schools across Laredo, Texas, using data measured by the Rio Grande International Study Center (RGISC). Photo by Sean Jimenez/South Texas Project

Midwest Sterilization Corporation has stated its emissions are within legal limits. The company did not respond to multiple requests for comment regarding their emissions and procedures and practices, including whether they have considered alternative sterilizers to ethylene oxide.

In response to the Texas Tribune investigation, the company said it remains in compliance with regulations, and touted its role in critical medical device sterilization services. “Midwest is taking all steps necessary to ensure that patients across the nation and residents locally remain safe,” the company told the Tribune in a statement.

Residents want answers

The Nevares family’s neighbor, Xavier Ortiz, was diagnosed in September 2024 with lymphoma.

There are reported cases of others who live near to the plant getting cancer, and many people and organizations, such as the Rio Grande International Study Center (RGISC), believe that the plant’s ethylene oxide emissions are linked to these illnesses.

No specific cancer case has been proven linked to the plant. However, activists and concerned residents point to studies that show Laredo to be a hotspot of ethylene oxide exposure.

Ortiz had no idea that emissions from the plant may be linked to his cancer until receiving a brochure from activists.

“They brought it to me and put it on the door. I checked the page and I told my wife, ‘Look, they say there's going to be a talk about this contamination, and the main effect it has is lymphoma,’” he said.

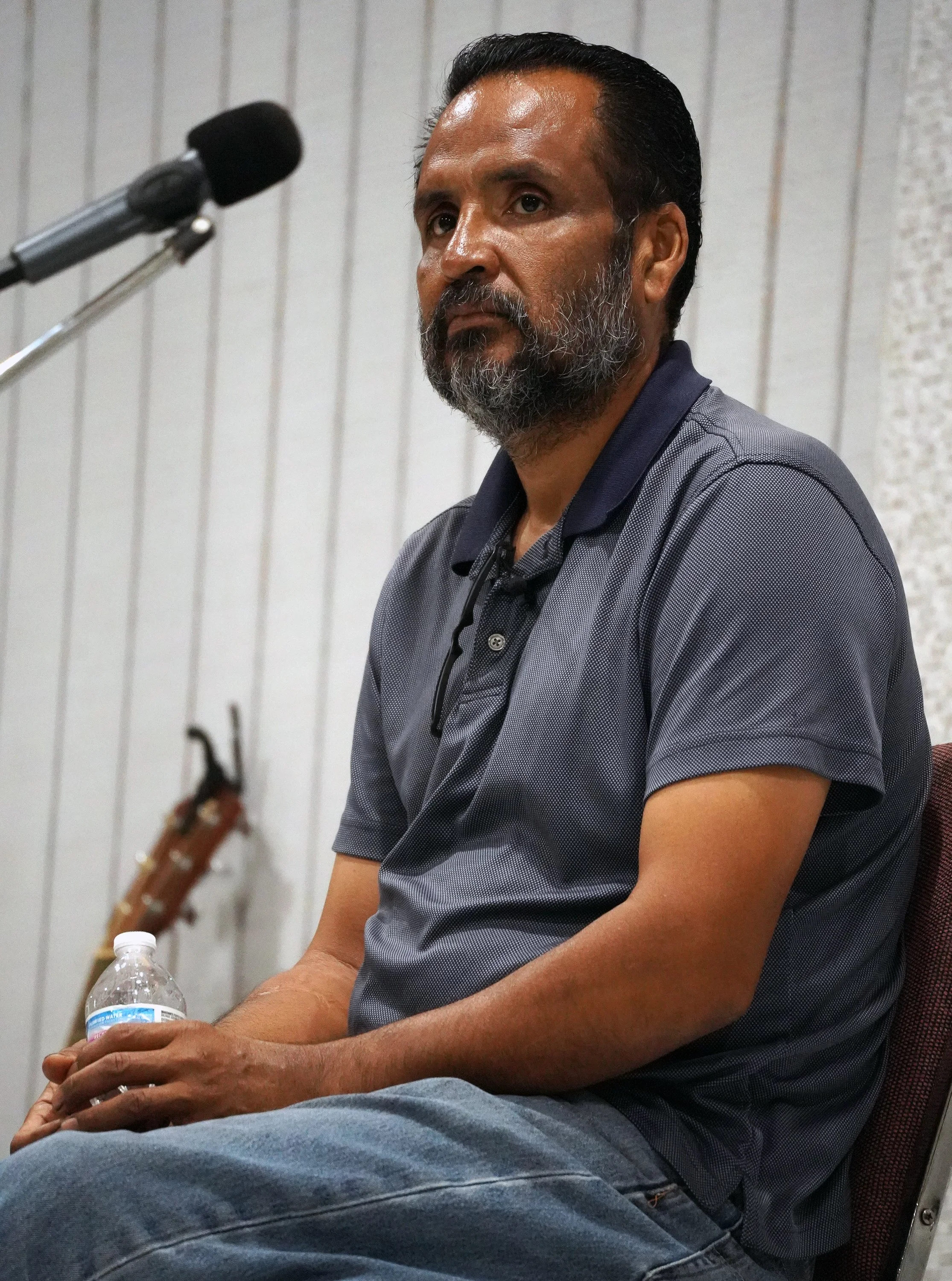

Javier Ortiz speaks about his diagnosis at Iglesia Cristiana Ministerio De Salvación in Laredo, Texas, on April 5, 2024. Photo by Sean Jimenez/South Texas Project

Ortiz wishes for a clear answer about the cause of his cancer, but while ethylene oxide is known to cause lymphoma, the lack of certainty bothers him.

“I have my children living in the house. I mean, I have more neighbors living there in the area,” Ortiz said. “It's not fair that more people would be contaminated.”

Ortiz's sickness affects him significantly on a daily basis.

“It affects my family’s finances, my health, my finances, my well-being, family problems due to the lack of money from not being able to work,” he said.

Chemotherapy treatments have left him stuck in bed for up to 12 days at a time, and his treatments, he stated, have been “very ugly.”

Even as he suffers, Ortiz recognizes that ethylene oxide is useful as a sterilizer. What he wants, he says, is a definitive answer as to the level of risk and for Midwest to properly mitigate it.

Stalled regulations

Under President Biden’s EPA administrator Michael Regan, the agency agreed to adopt new standards. The agency touted the new “final rule,” announced in March 2024, as historic.

However, following the transition to a new administration in Washington, the Trump EPA is rethinking the rules. Environmental advocates say there is a risk that the tighter regulations may never go into effect.

“This administration has taken a different approach to that industry, incredibly favorable [to it],” said Tricia Cortez, Executive Director of RGISC.

The Ethylene Oxide Sterilization Association, an industry trade group, had filed a legal action calling for a review of the final rule.

The organization Rio Grande International Study Center (RGISC) has found a localized source of toxic emissions in Laredo, Texas, possibly linked to the Midwest Sterilization Corporation. The company has claimed its ethylene oxide emissions are within legal limits. Photo by Sean Jimenez/South Texas Project

Meanwhile, EarthJustice – representing RGISC and others– petitioned to compel the EPA to enforce its 2024 final rule.

Amid the dueling petitions, the EPA –now under President Trump’s EPA administrator, Lee Zeldin– filed its own motion for a temporary suspension of the proceedings because “the agency has now determined that it wishes to revisit and reconsider.”

Support the voices of independent journalists.

|

The motion for abeyance, as it is known, was filed on March 25, just days after EPA announced publicly that it will reconsider multiple air pollution emissions standards, including those related to the commercial sterilization of medical devices.

“The EPA is going to take that new rule and they’re basically going to take it back and just rewrite it,” Cortez said.

Lillian Zhou, an EarthJustice attorney representing the petitioners in the lawsuit, said the process is typical of cases that transition between administrations.

“A lot of the time, a new administration will ask pending lawsuits to be put in abeyance so they could go back and change whatever the underlying standards are,” Zhou said.

J.J. Nevares and his mother, Nidia Nevares, at the Father Charles M. McNaboe Park. Photo by Sean Jimenez/South Texas Project

In Laredo, that balance between protecting the environment and boosting American companies hits close to home.

“So all of these things are happening more at a national level, with the rule and the agency that regulates this air toxin that then impacts communities like ours here,” Cortez said. “In terms of how a local community can protect itself or act toward these kinds of companies is somewhat limited. You know, you have to have these two battles, the national one, and then what’s happening on the local front as well.”

—

Olivia Biggs, Avery Foster and Callaghan Mitchell are journalism students at Texas A&M University. David Perez and Sean Jimenez are students at Texas A&M International University.

Olivia Biggs is a senior journalism major at Texas A&M University. She has been a contributor to The Battalion student newspaper for sports reporting and is currently pursuing Life and Arts reporting. She was selected in 2025 to The South Texas Project, a field reporting trip to the Texas-Mexico border. @oliviabiggss

Avery Foster is a journalism major and communication minor at Texas A&M University from Pasadena, Texas. She is a senior graduating in Spring 2026 with a strong interest in investigative journalism and research. Foster currently works as a content contributor at KAMU-FM, Texas A&M’s public radio station, where she helps produce stories and engage audiences across multiple platforms. She is passionate about uncovering complex issues and delivering impactful journalism. @averyfoster.15

Callaghan Mitchell is a senior Journalism major at Texas A&M University. He has spent time working with The Battalion student newspaper and Texas A&M Athletics’ 12th Man Productions. He has a strong interest in sports journalism but has covered various topics including environmental issues and opinion pieces. Callaghan is looking to expand his horizons by branching out into PR work. @CallaghanM92789

|

David Pérez Jr. is a graduate of Texas A&M International University where he earned a Bachelor of Arts in Communication with a minor in Pre-Law. He is a former staff writer for The Bridge student newspaper at TAMIU where he covered campus events and news. David was born and raised along the border of Texas and Mexico in Laredo. While growing up in his community, David gained a passion for storytelling to which he applies to filmmaking. David’s hobbies include outdoor activities such as hiking and he practices photography. @david.perez.956 |

Sean Jimenez is an aspiring environmental photojournalist and a junior in Texas A&M International University in his hometown of Laredo, Texas. He is working towards a major in communications with a focus in media production and a minor in environmental science. He is currently the Director of Photography and Assistant Editor of "The Bridge", TAMIU's student run newspaper. He aims to shine light on underrepresented communities and animal populations facing environmental struggles due to climate change and urbanization.

Mariano Castillo is a Professor of Practice in journalism at Texas A&M. Previously, he held several roles at CNN, from writer to fact check editor to director of standards and practices. @mariano_tamu

Rodrigo Cervantes is an award-winning bilingual journalist and communications strategist with extensive experience in the U.S., Mexico, and internationally. He has contributed to outlets such as NPR, CNN, The Los Angeles Times, and the BBC. Cervantes led KJZZ’s Mexico City bureau, where he launched the first overseas bureau for a U.S. public radio station. He also served as Business Editor-in-Chief for El Norte, part of Grupo Reforma, Mexico’s leading newspaper company. In Georgia, he led the newsroom of MundoHispánico, then the state’s oldest and largest Latino publication, under The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. His work has been recognized with RTDNA Murrow Awards and José Martí Awards from the National Association of Hispanic Publications (NAHP). He is the former Secretary of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists (NAHJ) and currently serves as co-managing editor of palabra, and as a clinical assistant professor at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication. @RODCERVANTES