Between the Observer and the Participant: He Follows ICE Across the Country, Fearing to Bear Witness

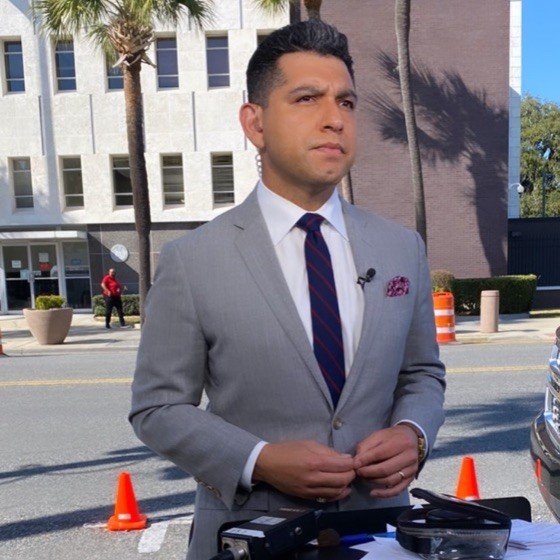

A federal agent points a weapon at journalist Nick Valencia (brown jacket) in front of a hotel, during a noise demonstration protest in response to A federal immigration enforcement operations in Minneapolis on Sunday, Jan. 25, 2026. (AP Photo/Adam Gray)

A LATINO INDEPENDENT JOURNALIST AND FORMER CNN CORRESPONDENT REFLECTS ON HIS EXPERIENCE MEETING FACE-TO-FACE THE ANTI-IMMIGRANT RHETORIC FROM LA TO MINNEAPOLIS.

Haga clic aquí para leer esta columna en español.

Words by Nick Valencia, @nickvalencianews

Edited and translated by Rodrigo Cervantes, @RODCERVANTES.

—

Immigration has followed me for most of my career, whether I wanted it to or not.

In newsrooms, it’s often the story you get assigned when you are a Brown reporter, not because of expertise, but because of identity. You are Latino, so you are expected to get immigration. Editors rarely say it outright, but everyone understands the logic. It’s good “casting.”

That’s the truth, as harsh as it sounds.

There were times when covering immigration made sense for me. But there were other moments when I was pulled aside and asked whether I really wanted to be “a Brown person covering Brown people.”

I spent years deliberately chasing stories that had nothing to do with people who looked like me, trying to prove that I could. I was trying to escape the quiet runway that had been built beneath my feet.

And yet, here I am.

Subscribe to palabra’s newsletter

Over the last two decades, across five presidential administrations, I’ve covered immigration more closely than most journalists in this country. I’ve seen children in cages. I reported on the Obama administration’s treatment of unaccompanied child minors. I’ve been on the border countless times, not just when it was politically convenient. And now, I’m documenting the social and psychological fallout of federal immigration officers fanning out across the United States once again.

In June 16, 2012, Myisha Areloano, Adrian James, Jahel Campos, David Vuenrostro, and Antonio Cabrera camped outside of the Obama Campaign Headquarters in Culver City, California, in protest of President Obama's immigration policies and in hopes of getting him to pass an executive order to halt discretionary deportation. (AP Photo/Grant Hindsley)

Right now, President Donald Trump’s mass deportation policy is the defining story of our lifetime. That’s true regardless of the color of our skin, whether it’s White or just a shade darker than our neighbors’. The trauma being inflicted doesn’t stop with Latino communities. It radiates outward. It reaches friends, allies, coworkers, classmates, and neighbors. It hits people who love us, and people whose lives intersect with ours every day.

In America today, that ripple effect feels unavoidable.

The familiar rebuttal to Trump’s mass-deportation policy is numerical. President Barack Obama deported more immigrants than nearly any other modern president, with estimates ranging from 300,000 to 400,000 removals per year (an estimate of 3.1 million people in total). Obama’s record is not without moral stain; his administration mishandled the surge of unaccompanied children at the border, and deportations did fracture families.

And yet, even at the height of those numbers, there was no evident atmosphere of sanctioned cruelty, no masked agents operating like secret police, no deliberate campaign to terrorize entire communities into silence. Federal agents were not hiding their faces as if it was an official part of their uniform; they were not stalking neighborhoods as phantoms. And that, more than any spreadsheet, is the line between enforcement and something far darker.

One of the quiet costs of working in a mainstream newsroom is that your instincts are often filtered, sometimes softened, by what the institution is prepared to defend. There are stories you can tell and stories you’re encouraged to angle just “slightly” differently. Over time, you learn where the invisible walls are.

People gathered outside Los Angeles City Hall in a "National Shutdown" protest against US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) on January 30, 2026. (Photo by Qian Weizhong/VCG via AP )

As journalists, we never want to become part of the story. It’s one of the unwritten rules of our profession. The last seven months have made that rule feel almost naïve.

What I’ve learned, instead, is that sometimes the best advice we can take is our own.

For years, I’ve told younger journalists the same thing: bet on yourself. Take the risk, if you truly believe in the work. That belief is how I rose from teleprompter operator to correspondent at CNN. And it’s how I’m now using my own experience, strength, and hope to try to lead in this new media space, at a moment when my community is being openly targeted and persecuted.

That clarity fully settled in when Alex Pretti was killed.

That day, I was one of the journalists closest to the action. I felt fully embedded, and I was reporting it all on the same iPhone I’m typing this story on now.

It took an hour and a half before I saw a large television camera. Not because I wasn’t looking, but because I was that close. With nothing but a phone in my hand, I tried to give people a perspective they otherwise wouldn’t have had. Not a polished one. Not a distant one. But a human one. Immediate, unfiltered, and honest.

That’s when it fully clicked: this is what independent journalism looks like now. Agile. Embedded. Uncomfortable. Sometimes frightening. Often lonely. And absolutely essential.

As journalists, we never want to become part of the story. It’s one of the unwritten rules of our profession. The last seven months have made that rule feel almost naïve.

That truth crystallized the morning of January 23, before I boarded a flight to Minneapolis. It wasn’t about clashes or chaos: I’ve found myself in those moments repeatedly in my career, and I know how to move through them. This fear was quieter, yet heavier. It was the fear of driving around as a Brown man on the streets of Minnesota during what is now the largest federal immigration operation in the history of the United States.

That fear didn’t come out of nowhere. It followed seven months on the road, alone, telling stories that others briefly enter before moving on. I’ve been in communities where immigration enforcement is no longer abstract policy but lived reality. Places where the line between law and trauma has all but disappeared.

I’ve been trying to meet “that moment” because there is one to meet. That consistency, more than anything else, has become a big part of why this work has broken through. It builds trust. And trust is the currency of journalism.

But the reality is that, when the systems you’re covering begin to blur the line between observer and participant, between reporter and target, you don’t get to choose neutrality in the way newsrooms once imagined it. You choose presence. And you keep going.

I never wanted to be part of the story. But just in case that story ever comes for me, just in case the Feds ever do, I now carry a copy of my birth certificate in my wallet. That is something I did not do a year ago. Because now, when it comes to immigration in America, it feels like I am part of the story, whether I like it or not.

Nick Valencia/palabra

Nick Valencia is a veteran journalist with more than two decades of experience as a street level correspondent. In June 2025, after 19 years at CNN, he launched his own media company. In a matter of months, he garnered more than 50+ million views and established himself among the top new news media platforms in the country, according to the Pew Research Center. A proud Los Angeles native, Nick first started reporting for his high school newspaper at 14. He is a graduate of USC’s Annenberg School and recipient of the inaugural “Sí Se Puede Excellence in Leadership Award” from NAHJ, where he served as Vice President and twice as President of the Atlanta chapter. He also founded the Latino Media All Stars, a 750+ member wellness-focused run club for media professionals. @nickvalencianews

Rodrigo Cervantes/palabra

Rodrigo Cervantes is an award-winning bilingual journalist and communications strategist with extensive experience in the U.S., Mexico, and internationally. He has contributed to outlets such as NPR, CNN, The Los Angeles Times, and the BBC. Cervantes led KJZZ’s Mexico City bureau, where he launched the first overseas bureau for a U.S. public radio station. He also served as Business Editor-in-Chief for El Norte, part of Grupo Reforma, Mexico’s leading newspaper company. In Georgia, he led the newsroom of MundoHispánico, then the state’s oldest and largest Latino publication, under The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. His work has been recognized with RTDNA Murrow Awards and José Martí Awards from the National Association of Hispanic Publications (NAHP). He is the former Secretary of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists (NAHJ) and currently serves as co-managing editor of palabra, and as a clinical assistant professor at Arizona State University’s W. Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication. @RODCERVANTES