Burned Out Latinos: How Fire Disasters Leave One of LA’s Largest Communities Behind… And How To Avoid It

Images by Emmanuel Olguín and CalFire. Photo illustration by Yunuen Bonaparte for palabra

California’s catastrophic wildfires have taken a heavy toll on Latino families and businesses, yet they’ve also sparked lessons in rebuilding and renewal.

Editor's note: This opinion column is co-published with Lotus Rising LA, a Los Angeles-based non-profit dedicated to helping families who lost their homes in the wildfires.

Haga clic aquí para leer este reportaje en español.

For many first-generation Latinos like myself, the idea of a wildfire threatening your house once felt like something straight out of a movie. That was until last January.

Unlike most American towns and cities, suburban neighborhoods in many of our hometowns in Latin America are dense, with most of our buildings made of fire-resistant materials like brick or cement. Help during a catastrophe often comes from camaraderie, with quick responses provided mainly by neighbors and family rather than authorities.

Don’t get me wrong: wildfires do exist in Latin America and can be devastating. But in Southern California, they are a recurring nightmare that feels surreal, frightening, and unfamiliar for many of us. Unlike Latin America, the response here in California relies almost entirely on the government.

Part of the problem we face in California is a lack of information, which affects most of us, whether you are a recent immigrant or part of a multigenerational Latino family. This, along with cultural, linguistic, ethnic and socioeconomic barriers, keeps the community disproportionately vulnerable during these catastrophes. Latinos in the Los Angeles metro area are more likely to be exposed to fire risk while systematically underserved when it comes to prevention, response and recovery.

According to a study from the UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Institute, at least 74,000 Latinos were affected by wildfires earlier this year. That’s about one-fourth of the total population impacted. The same study suggests that, regardless of how significant that number is, emergency management systems have historically failed to address the specific needs of Latino communities, discouraging them from seeking assistance.

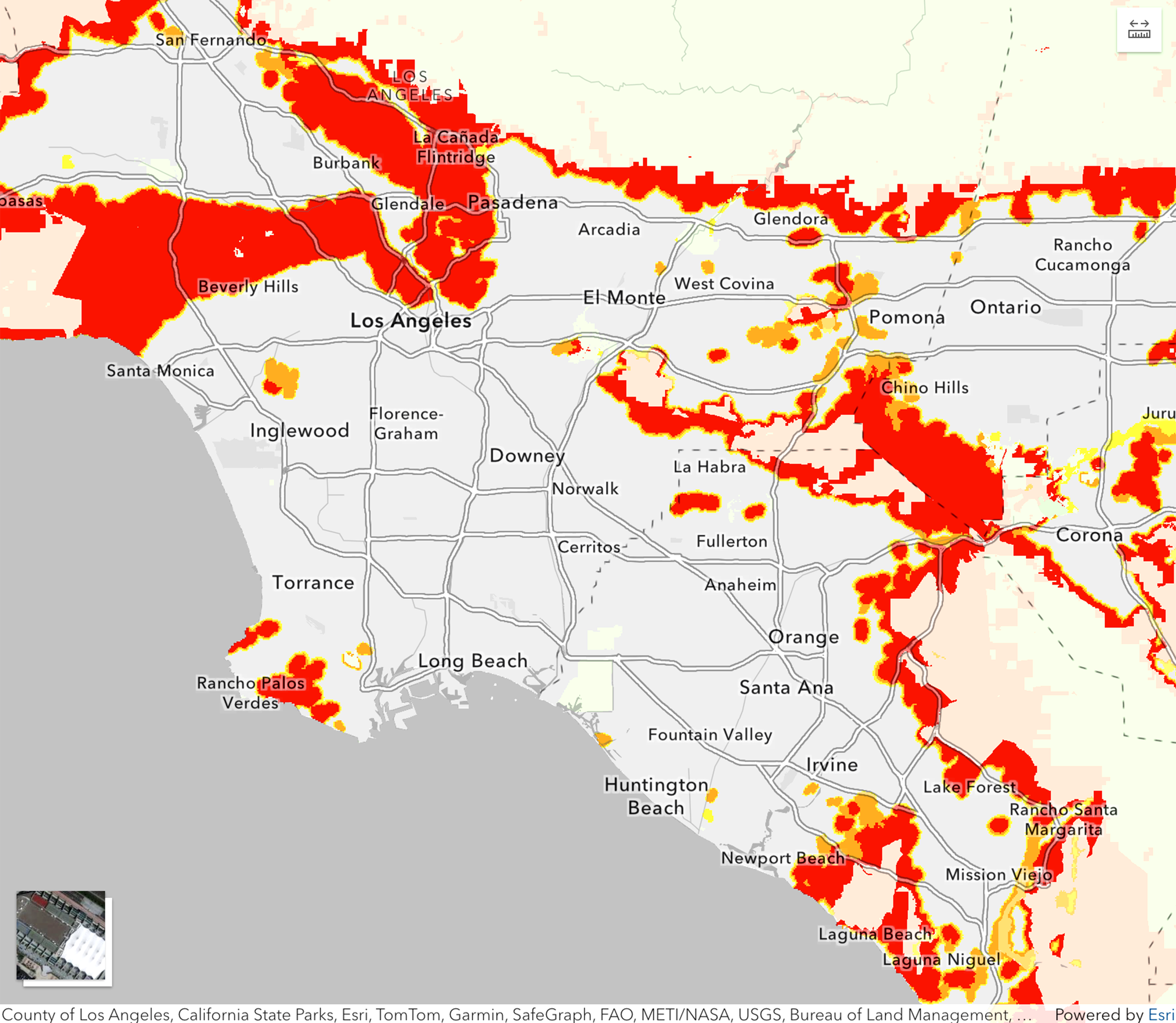

The Fire Hazard Severity Zone (FHSZ) map of Los Angeles. The FHSZ map is developed using a science-based and field-tested model that assigns a hazard score based on the factors that influence fire likelihood and fire behavior. Image courtesy of CalFire

In addition, “language barriers, fears of immigration enforcement, as well as concerns about being labeled a public charge, still limit the Latino community’s search for support,” the study says.

The situation has worsened in recent years, given the political tensions and social unrest stemming from the Trump administration. Current immigration policies and federal tactics have increased fear and mistrust of authorities among Latinos across the region. The continuous and often unpredictable raids conducted by ICE (widely reported as being influenced by xenophobia or racism) have left many feeling more alienated than ever.

The Altadena Resident Impact Survey and Evaluation (ARISE) compiled experiences and opinions of residents after the Eaton Fire. Nearly 80% of Latino residents reported feeling ignored, compared with white residents, by more than 10 percentage points. How will Latinos build trust in the system to face disastrous wildfires in the future, when many already feel abandoned or persecuted by the government?

Support the voices of independent journalists.

|

Fear and lack of information are not the only challenges. Many Latino households and businesses affected by fires are also severely impacted by an already struggling economy, worsened by inflation. Poor access to or knowledge of financial tools, such as insurance, emergency funds, or savings accounts, heavily affects how the community recovers from catastrophe.

The ARISE survey shows that Latino small businesses and households in that area often face significant gaps in emergency preparedness and have limited access to safety-net programs during times of crisis. But the reality is not different across the entire state. According to a 2023 survey to small businesses conducted by UCLA’s Latino Policy and Politics Institute, more than one-fourth of small businesses in California reported having no flood, earthquake or fire insurance, despite such coverage offering crucial financial protection.

A recent story published by palabra documented cases of several Latino businesses in Altadena facing devastation after fires destroyed their shops, homes and livelihoods. While some found support through community solidarity, others had to take out loans, adding an extra burden to an already precarious situation.

Misinformation and overconfidence also play a role in the lack of insurance. One interviewee in the palabra story explained that he never purchased insurance because he never thought something like that could happen.

Employees of G&S Junk Removal, a Latino-owned business, trim branches at a wildfire-damaged home in Altadena. Despite high demand for clean-up services, many small businesses struggled to stay afloat in the aftermath of the fires. Photo by Jesús Jank Curbelo for palabra

Altadena is just one example of what Latinos in other regions may be facing.

So, what can we do?

We may not build concrete homes everywhere like in Latin America, but we can push for public and private investment in fireproofing vulnerable homes. Funds could be directed toward retrofitting older buildings, clearing brush and installing hydrants. This is not charity, but smart policy to prevent catastrophes.

Fire codes should be reinforced in high-risk, low-income areas, particularly because many negligent landlords exploit tenants’ language barriers or immigration status to keep their properties uninspected or unsafe.

At the same time, education within the community is critical. Latinos should continue relying on the solidarity that defines our culture during catastrophes, not only to face disasters as they come, but to prepare for them. Professional training on keeping properties safe and knowing what to do in case of a fire would greatly improve readiness. Local volunteer brigades can be trained through programs such as Community Emergency Response Teams.

Neighborhood-driven training should go beyond safety. Financial and insurance guidance from experts can also help households and businesses prepare.

A volunteer brigade affiliated with the Pasadena Community Job Center cleans up the City of Pasadena, California. Among the most vulnerable members of the workforce, a group of day laborers — many of them Latino immigrants — went out into the streets of Los Angeles as volunteers to help with cleanup efforts in the wake of the fires. Photo by Jesús Jank Curbelo for palabra

To fight fear and discrimination, the government must hire and promote more Latino firefighters and leaders to confront the wildfire crisis. A fire response is only as strong as its connection to the people it serves. FEMA and Red Cross centers should be designated immigration-safe zones, with no law enforcement data sharing, so aid remains available regardless of legal status.

During recent wildfires, Latinos have made up a large portion of California’s firefighting workforce and volunteer base. We fight the fires. We help those in need. We rebuild homes and businesses. We love our cities and our communities. But when our own properties burn, we are too often left on our own. We cannot continue to be treated as collateral damage.

Fires do not just consume homes: they expose inequities and reveal our character. We have proven we can do good.

But we can do better. And we can demand better.

—

Rodrigo Cervantes is an award-winning bilingual journalist and communications strategist with extensive experience in the U.S., Mexico, and internationally. He has contributed to outlets such as NPR, CNN, The Los Angeles Times, and the BBC. Cervantes led KJZZ’s Mexico City bureau, where he launched the first overseas bureau for a U.S. public radio station. He also served as Business Editor-in-Chief for El Norte, part of Grupo Reforma, Mexico’s leading newspaper company. In Georgia, he led the newsroom of MundoHispánico, then the state’s oldest and largest Latino publication, under The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. His work has been recognized with RTDNA Murrow Awards and José Martí Awards from the National Association of Hispanic Publications (NAHP). He is the former Secretary of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists (NAHJ) and currently serves as co-managing editor of palabra, and as a clinical assistant professor at Arizona State University’s W. Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication. @RODCERVANTES

Belinda Chen is an editor and native Angeleno with 20+ years in public health, research, and advocacy. She brings a passion for justice, healing, and yoga to support her city’s recovery. @belinda_yogi