Tariffs vs. Robots: Why Trump’s Trade War Can’t Bring Back the Jobs of the Past

Rows of injection molding machines at one of Óscar Cázares' high-tech manufacturing plants in Tultitlán, State of Mexico. Photo courtesy of Industrias Cazel

Automation and cost barriers defy the promise of reshoring, leaving border economies in limbo as factories stay put in Mexico.

Editor’s note: This story was co-published with Puente News Collaborative in partnership with palabra. Puente News Collaborative is a bilingual nonprofit newsroom, convener, and funder dedicated to high-quality, fact-based news and information from the U.S.-Mexico border.

As the head of a mid-sized auto parts company, Óscar Cázares had long considered how to respond if President Donald Trump slapped tariffs on Mexican-made components.

One option was clear: move some production to the United States, fulfilling Trump’s much-touted promise to revive American manufacturing and create new jobs.

But after weighing the costs, he dismissed the idea.

“Relocating my plants — robots and all — would come at a brutal cost,” said Cázares, whose factories throughout Mexico, including at the border with the U.S., produce dashboards, door panels, armrests, glove compartments, and many other components for the automotive industry. “There’s no way to justify it, even with tariffs in place.”

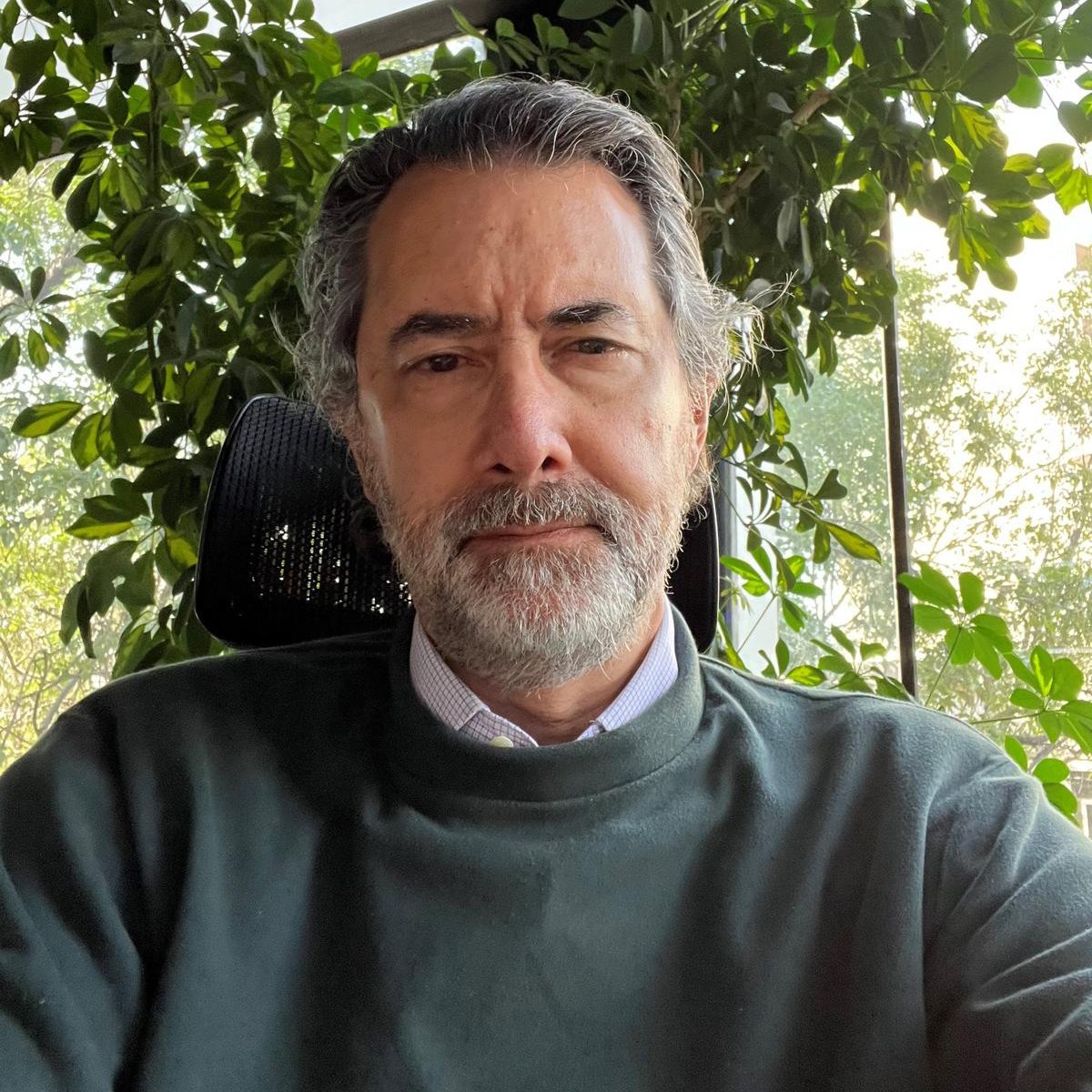

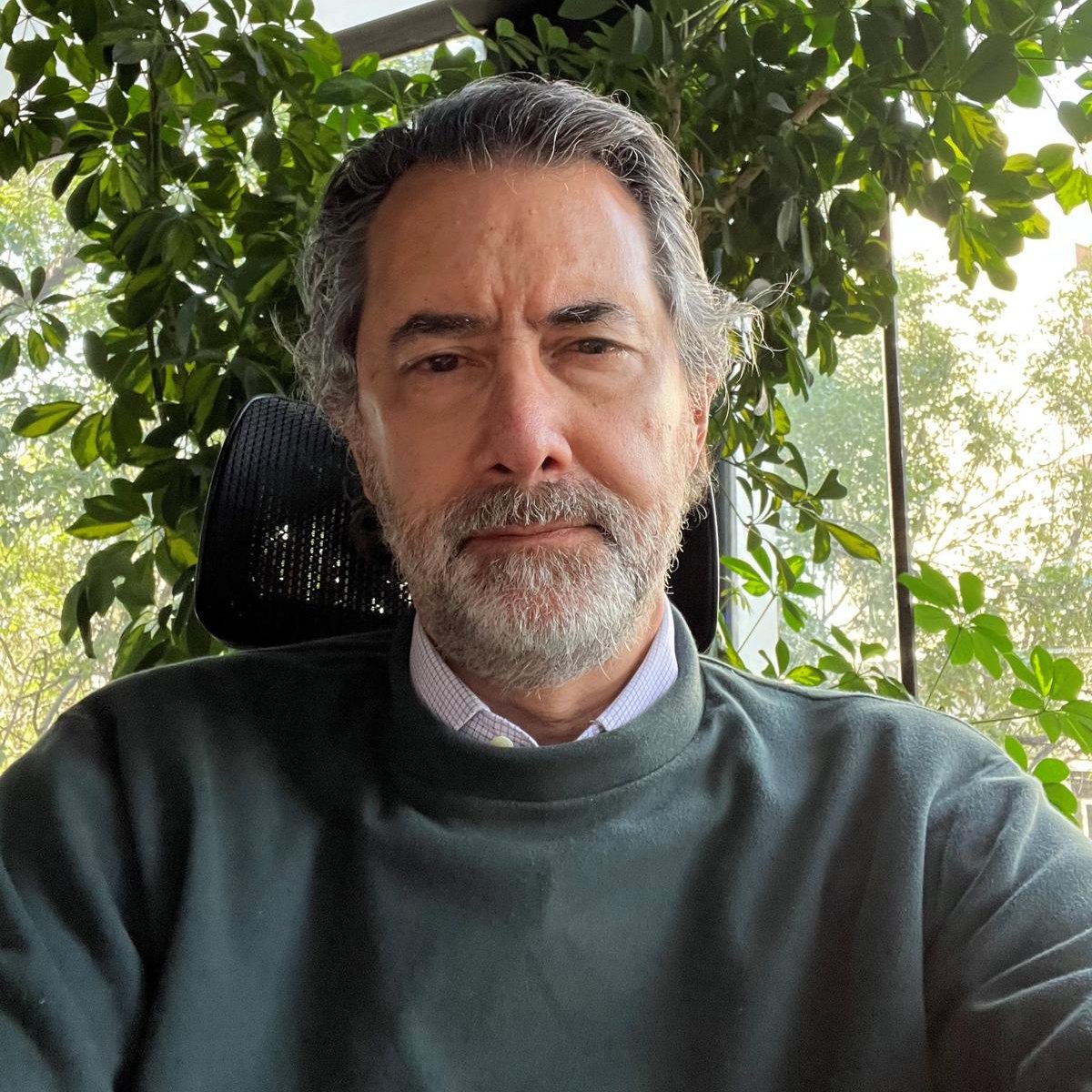

Óscar Cázares at his company in Tultitlán. His company, Industrias Cazel, has nearly 1,000 employees at plants throughout Mexico. Photo courtesy of Industrias Cazel

His decision reflects a twofold reality check for Trump, who has long argued that by raising the price of foreign-made goods through steep levies, manufacturers in Mexico and elsewhere would shift operations to the U.S. That strategy, implemented by his administration, would bring back millions of industrial jobs lost over the past four decades.

But most economists and trade experts contend that Trump’s logic is far off the mark. A panel of federal judges recently blocked President Trump from imposing most of his tariffs on China and other U.S. trading partners. The judges found that the president had overstepped the authority granted to him under the 1977 International Emergency Economic Powers Act.

If it holds up on appeal, the panel’s ruling severely undercuts the logic and the negotiating strategy the Trump administration has been employing in trying to overhaul the international trade system.

Trump officials have said the case will likely go to the U.S. Supreme Court, “sooner, rather than later.”

‘A lot of projects are still on hold or postponed or canceled because of the uncertainty of the tariffs and the economic environment.’

Meanwhile, business leaders consider trade war worries far from over. The court’s ruling will likely further muddle decision-making for countless trade-dependent businesses, including those along the U.S.-Mexico border.

In the border town of Santa Teresa, New Mexico, far more immediate concerns cloud the once-strong synergies between both countries. The effects of Trump’s economic policies are overhauling the historic symbiotic relationship between factories in Mexico and speculative warehouse spaces on the U.S. side.

The spec warehouses in the dry and sandy Santa Teresa desert are prime real estate for goods arriving through the nearby Santa Teresa Port of Entry. Over the past few years, demand for these types of spaces outpaced the supply, said Jerry Pacheco, president of the Border Industrial Association. Now, just as supply is finally catching up, that progress risks being lost.

Shipping containers near the Santa Teresa and San Jerónimo Border Crossing between New Mexico and Mexico. Photo by Sandra Sadek/Puente News Collaborative

In late 2023, Taiwanese auto parts supplier Hota’s announcement of a 30-acre campus in Santa Teresa was a huge economic investment for the border town of about 6,000 residents. On the table: 350 new employees and a $99 million investment into the state, for a combined $4.3 billion economic impact over 10 years.

Two years in, the project’s finish line is vanishing into the horizon.

“A lot of projects are still on hold or postponed or canceled because of the uncertainty of the tariffs and the economic environment,” Pacheco said.

And as trade with Mexico becomes more volatile, it’s the border towns that are bearing the brunt of the impact.

“It’s like killing an ant with a sledgehammer,” Pacheco adds. “That’s not the way you do things.”

He also cautioned that automation may translate into lower wages on both sides of the border.

“You are looking into a whole set of dynamics. A lot has changed in 30 years.”

An industrial park in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, directly across the border from El Paso, Texas. As trade with Mexico becomes more volatile, border towns are bearing the brunt. Photo by Omar Ornelas/El Paso Times/Puente News Collaborative

Indeed, manufacturing today generally is not what it was three decades ago when the U.S. free trade system kicked into high gear with the adoption of the North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA.

Even as some U.S. factories shifted to Mexico, China, and elsewhere, their once labor-intensive production became increasingly automated, these experts contend. In many factories, the heavy lifting is now done by motion control systems, sensors, robotic arms, autonomous guided vehicles, and advanced vision technologies —not workers.

“The decline in manufacturing employment is mostly driven by automation and productivity growth,” Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman said recently on ”The Ezra Klein Show” podcast.

Now, should production be returned to the United States, many of the jobs lost will not be regained.

For small and mid-sized auto parts producers, moving highly automated plants from Mexico to the U.S. is prohibitively expensive. Relocation costs aside, the skilled engineers who now run these robot-heavy facilities command much higher wages north of the border.

Commercial trucks wait to enter the U.S. at the Santa Teresa Port of Entry in New Mexico, which ranks among the top commercial ports in the country, facilitating over $31 billion in trade annually. Photo by Omar Ornelas/El Paso Times/Puente News Collaborative

Smaller Mexican companies can find highly qualified labor needed to operate automated factories at little more than half of U.S. wages, Cázares said. Mexico currently ranks eighth in the world in terms of the engineering, manufacturing, and construction graduates produced annually.

Cázares’ company, Industrias Cazel, employs nearly 1,000 people at plants in Tultitlán, on the outskirts of Mexico City; in nearby Querétaro state; and in the northern industrial center of Monterrey. The plants serve different car manufacturers like Stellantis, Nissan, Honda, and Volkswagen, in Mexico and abroad.

Top operators at his plants earn between $25,000 and $30,000 a year, Cázares said, and that the same job in the U.S. would cost him at least $80,000.

“Moving north just doesn’t make sense, unless my clients are ready to pay three times more,” he added.

Labor once comprised as much as 90% of an auto parts maker’s costs. Today, wages account for 30% or less of production costs, said Cázares, a former president of Mexico’s National Autoparts Industry Association, known as INA.

‘It’s really hard to see large numbers of jobs being created … You’ve probably seen what a modern automobile factory looks like, there aren’t workers standing there anymore. They’re machines.’

Mexico today has about 2,500 auto parts makers that employ nearly 900,000 workers, according to INA.

Some production, like wiring harnesses for autos and other products, will always require intensive labor. But many Mexican auto parts makers have made major technological strides in recent years.

Welding, assembly, and inspection jobs that once required human hands are now handled by machines in most highly or fully automated auto plants.

The transformation is even more pronounced in the United States.

For example, the Tesla Gigafactory opened in Austin, Texas, in 2021, employing fewer than 3,000 assembly line workers to produce as many as 300,000 passenger cars and Cybertrucks annually.

In contrast, Ford’s Chicago assembly plant, modernized in the early 2000s, employs nearly 5,000 workers to produce an equal number of vehicles. Despite its upgrades, employment at the Ford plant reflects an earlier phase of automation, with fewer labor-saving technologies than Tesla’s Austin facility.

Ford's Chicago Assembly Plant added 600 advanced robots and new manufacturing tech in 2019 to boost production efficiency. Ford's use of advanced technology in their plant began in the early 2000s. Photo by Sam VarnHagen/Courtesy of Ford Motor Company

A factory opened in 2022 in the Turkish province of Gemlik. That fully automated facility is owned by Togg, an auto conglomerate founded in 2018 by five Turkish companies, and which produces 175,000 electric sport utility vehicles annually while employing only 500 manufacturing workers.

“It’s really hard to see large numbers of jobs being created” in the U.S., said Harold James, a Princeton University economist, on ”The Rachman Review” podcast. “You’ve probably seen what a modern automobile factory looks like, there aren’t workers standing there anymore. They’re machines.”

During his first administration, Trump blamed NAFTA for U.S. job losses, especially to Mexico. He forced a renegotiation of the pact, resulting in the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, or USMCA, which took effect five years ago.

The new trade pact has delivered two notable wins for U.S. automakers. It raised the threshold of North American content required for tariff-free trade to 75%. And it mandated that 40% to 45% of a vehicle be produced by workers earning at least $16 an hour, aimed at neutralizing Mexico’s low-wage advantage.

Those provisions slowed but didn’t stop the growth of Mexico’s automotive industry, which currently sells about three million light vehicles annually to U.S. consumers.

‘The manufacturing in Mexico is labor-intensive, so you cannot replace it with automation yet.’

Yet the renegotiation served to squelch the construction of new vehicle assembly plants in Mexico. More than a dozen such plants were built in the country around the turn of this century. Today, only one new factory, by truck maker AB Volvo, is underway in Monterrey.

Tesla, meanwhile, suspended construction of a new Monterrey plant, citing uncertainty over U.S. tariff policy.

Support the voices of independent journalists.

|

However, some experts like Cinthya Caamal, an economics professor at the Autonomous University of Nuevo León, believe that should free trade agreements like USMCA collapse, the impact felt in Mexico might not be as harsh as other historic events like the COVID-19 pandemic.

That’s because the automated replacement of factory workers in Mexico might not be as disruptive as expected in the U.S., she said. The technology remains expensive and may not meet the needs of companies operating in Mexico.

“We are still behind that technology. The manufacturing in Mexico is labor-intensive, so you cannot replace it with automation yet. We also have highly skilled labor that is cheap.”

Workers assemble electronic components at the Lacroix factory in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, that are used in GMC trucks. Photo by Omar Ornelas/USA Today

Even Trump administration officials believe that any plants built in the U.S. will be highly automated.

“They’re going to be mechanics, HVAC specialists, electricians,” Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick said of reshored jobs on CBS’ “Face the Nation.”

“The tradecraft of America — our high school–educated Americans, the core of our workforce — is going to see the greatest resurgence of jobs in American history, working in these high-tech factories,” Lutnick added.

Indeed, U.S. purchases of industrial robots, from both domestic and foreign suppliers, have more than doubled in the past decade. The United States is now the world’s third-largest market for industrial robots, after China and Japan.

No other industry uses robotics more intensively than auto manufacturing, the cradle of modern U.S. industrial processes. As the sector shifts toward hybrid, electric, and autonomous vehicles, reliance on robotics is only accelerating.

Injection molding machines at Industrias Cazel manufacturing plants. Photo courtesy of Industrias Cazel

“Today, robots are playing a vital role in enabling this industry’s transition from combustion engines to electric power,” said Marina Bill, president of the International Federation of Robotics (IFR). “Robotic automation helps car manufacturers manage the wholesale changes to long-established manufacturing methods and technologies.”

As of 2023, U.S. automakers had deployed 1,287 robots per 10,000 manufacturing workers, according to the IFR. That’s more than China but still only about half that of competitors like Germany or South Korea, the global leader in robotics use.

“If many new factories are built in the U.S., this could provide a boost for the robotics industry,” said Patrick Schwarzkopf, managing director of VDMA Robotics + Automation in Germany. “Otherwise, they will not be competitive.”

—

Eduardo García established Bloomberg’s Mexico bureau in 1992 and served as its leader until 2001, overseeing the agency’s award-winning coverage in the country. In 2001, he embarked on a new venture by founding his own news organization, Sentido Común. @egarciascmx

Sandra Sadek is a freelance journalist based in New York. She is studying international reporting at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York (CUNY). Previously, she was a Report for America Corps member in North Texas. @ssadek19

Dudley Althaus has reported on Mexico, Latin America, and beyond for more than three decades as a staff newspaper correspondent. Beginning his career at a small newspaper on the Texas-Mexico border, Althaus had an award-winning 22-year stint as Mexico City bureau chief of the Houston Chronicle. After a four-year run as a Mexico correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, Althaus covered immigration and border issues as a freelancer based in San Antonio for Hearst Newspapers. He has covered every Mexican presidential election since 1988, when Mexico's troubled transition to democracy began. @dqalthaus