No License, No Rights: The Underground Network Keeping Immigrants in a Georgia College Town Moving

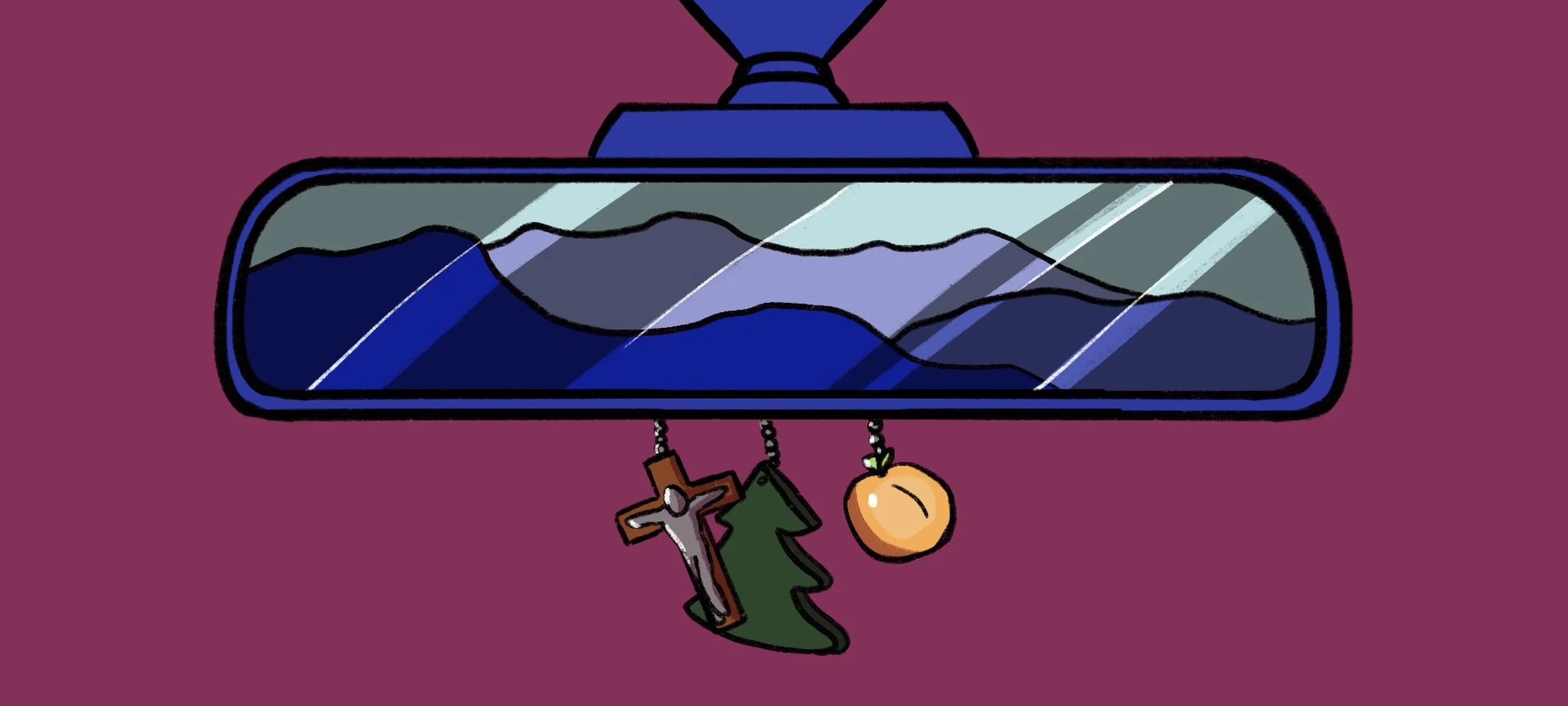

Illustration by Olivia Abeyta for palabra

They were told to “Go Hunting” for migrants, so these volunteers hit the road to protect them.

Alondra López, a graduate student at the University of Georgia, was troubled by the anti-immigrant rhetoric she said arose on campus following the brutal murder on February 22, 2024, of Laken Riley, an Augusta University nursing student, by an undocumented migrant from Venezuela. Riley’s murder drew national attention; the Laken Riley Law was the first piece of legislation President Trump signed in his second term and requires federal officials to detain any migrant charged or arrested in connection with a crime.

In the weeks following Riley’s murder on the University of Georgia campus in Athens, “The university environment became more hostile,” said López, a doctoral student in counseling psychology. In addition to friends telling her about verbal slurs and harassment against Latinos, López said she and her sister saw an anonymous post on a social media app that read, “I know where the migrants are. Let’s go hunting.”

To show tangible support for the Latinx community, Lopez, along with her sister and a friend, started a drivers’ pool.

Residents who lack a Georgia driver’s license and/or vehicles call a Google number to ask for rides. Volunteer drivers answer requests on Signal and give rides - whether to doctors’ offices, immigration court, or work. “We understood how severe it would be if somebody was stopped by the police and didn't have a driver's license,” López told palabra.

Athens Rides is now a project of the all-volunteer Athens Immigrant Rights Coalition. Nearly 100 drivers have signed up to offer rides, and they have given about 65 rides, “which is not a ton, but it's also 65 people that we were able to help, or many people get multiple rides,” said Eleanor Davis, who helps coordinate the program.

No national database tracks exactly how many of these allied-driver programs now operate in the United States. Gwen Frisbee-Fulton, a North Carolina-based writer and organizer, said that it is a good thing because these decentralized programs serve vulnerable populations. “If you had a national or more formalized program right now, you’d be under attack immediately,” particularly in an era of mass deportation, she added.

‘We are the poor people of this movement … We're the people who are doing (something) with nothing.’

Beto Mendoza, a co-founder of the Athens Immigrant Rights Coalition and Dignidad Inmigrante en Athens, said, unlike well-funded anti-immigrant groups, grassroots movements such as his do not have the time or resources to form coalitions with like-minded volunteers in other parts of the country.

“We do what we can do,” Mendoza said. “We are the poor people of this movement …We're the people who are doing (something) with nothing.”

Athens Rides appears to be the only such program in Georgia, said Kyle Gomez-Leineweber, former director of public policy and advocacy for GALEO (formerly known as the Georgia Association of Elected Officials). The nonprofit works for Latinx civic engagement in a state with an estimated 339,000 undocumented immigrants, according to figures from the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank based in Washington, D.C.

Mendoza said that because some Latinx workers migrate within the state to take short-term jobs in construction, it is hard to estimate exactly how many live in Athens. “It can be 20% … I don't know.” The U.S. Census Bureau, which has acknowledged widespread undercounting of African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans in its 2020 Census, estimated that 11.5 percent of residents in Athens-Clarke County, a consolidated city-county, are Latinx.

Illustration by Olivia Abeyta for palabra

In Georgia, as in 30 other states, undocumented residents cannot obtain a state driver’s license. Legislative efforts to allow undocumented residents to obtain drivers’ licenses in Georgia have stalled. The legal risks of driving without a license in Georgia are serious: if a person is caught four times, it is a felony.

The inability of undocumented residents to get drivers’ licenses has an economic impact, said Gomez-Leineweber. “People love to talk about how Georgia is the number one state to do business in … Our community, the Latino community, the immigrant community is the foundation for Georgia's biggest industries … Our community is consistently filling jobs, consistently doing the work that needs to be done while also facing barriers to get to do that work.”

The Athens Drives program is one way to protect human rights in a system that seeks ways to criminalize the Latinx community, Mendoza said.

Support the voices of independent journalists.

|

Tim Penning, a retired father of four, volunteers with Athens Drives. In March, he drove a mother and her three young children 90 minutes to federal immigration court in Atlanta. Penning decided to accompany the family into the courtroom on the 24th floor, a process that he said was confusing due to a lack of signage and clear explanation to visitors, even in English. Penning speaks no Spanish, and the mother speaks no English, but he found out later through an acquaintance that, “She was surprised that I stayed with them. She figured that I would just dump 'em at the door and then maybe come back around and pick them up later. And I thought, no, I can't do that. I've got to go all the way through with this. I couldn't have done otherwise.”

Part of Penning’s willingness to volunteer, he says, stems from his Catholic faith; he studied for the priesthood as a teenager. “I was in the Franciscan seminary, and one of the precepts of Franciscans is social justice.”

Adelheid Schmidt covers her bumper stickers - No Human is Illegal and Black Lives Matter - when she volunteers with Athens Drives so as not to draw attention to her vehicle. One time, she drove a 16-year-old mother to her newborn’s pediatric appointment, and while Schmidt doesn’t speak Spanish, the teenager spoke English.

Her motive for volunteering? “They're my neighbors,” Schmidt said.

Illustration by Olivia Abeyta for palabra

In the Athens Drives Volunteer training, confidentiality and safety are key. The handbook advises, “Never share any information about the households we work with.” “Do not ask your passenger about their documentation status. Keeping this information private is safer for both you and your passenger.” “Make sure your car is road-legal and your license, registration, and proof of insurance are up to date.”

For López, one of five children of carpet-factory workers, developing Athens Rides was a natural extension of her childhood in Dalton, Ga., in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. More than half of the residents are Latinx - many of them migrants and their families from Guanajuato in central Mexico, drawn to work in Dalton’s carpet, rug, and vinyl flooring factories, giving the city the moniker of Carpet Capital of the World.

López’s home community is of mixed immigration status and is currently represented in the U.S. House of Representatives by Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, an ardent supporter of stricter immigration policies.

“Dalton has, since I can remember, had the 287(g) policy where local sheriff's departments have to collaborate with immigration and customs enforcement directly,” one of a few counties in the state with such a policy, López says.

“And so we grew up with that.”

—

Allison Salerno is a multimedia journalist based in Athens, Ga. A graduate of the master’s program at Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism, she has been published in The New York Times and The Washington Post, among other outlets. Allison is a recipient of an Ñ award in 2024 from the National Association of Hispanic Journalists for a story on how Georgians are helping Venezuelan asylum seekers. She received another Ñ award in 2025 for a radio documentary on how immigrant farmworkers cope with extreme heat in Florida. You can find Allison at www.allisonbsalerno.com. @allisonbsalerno

Olivia Abeyta is a freelance illustrator and writer based in Chicago. She graduated from Northwestern University with degrees in Journalism and Latina and Latino Studies. Her work has been published in The Daily Northwestern and North by Northwestern Magazine. Abeyta was born and raised in Santa Fe, New Mexico. @artbeyta

Patricia Guadalupe, raised in Puerto Rico, is a bilingual multimedia journalist based in Washington, D.C., and is the co-managing editor of palabra. She has been covering the capital for both English- and Spanish-language media outlets since the mid-1990s and previously worked as a reporter in New York City. She’s been an editor at Hispanic Link News Service, a reporter at WTOP Radio (CBS Washington affiliate), a contributing reporter for CBS Radio network, and has written for NBC News.com and Latino Magazine, among others. She is a graduate of Michigan State University and has a Master’s degree from the Graduate School of Political Management at George Washington University. She is the former president of the Washington, D.C., chapter of NAHJ and is an adjunct professor at American University in the nation’s capital and the Washington semester program of Florida International University. @PatriciagDC