Mafalda’s Soup Rebellion: A Comic Strip’s Delayed Revolution in English

Images courtesy of Elsewhere Editions. Photo illustration by Yunuen Bonaparte for palabra

The beloved Argentine comic strip, with its sharp political wit and youth’s view of injustice, finally gets an English translation — just in time for a new era of global upheaval.

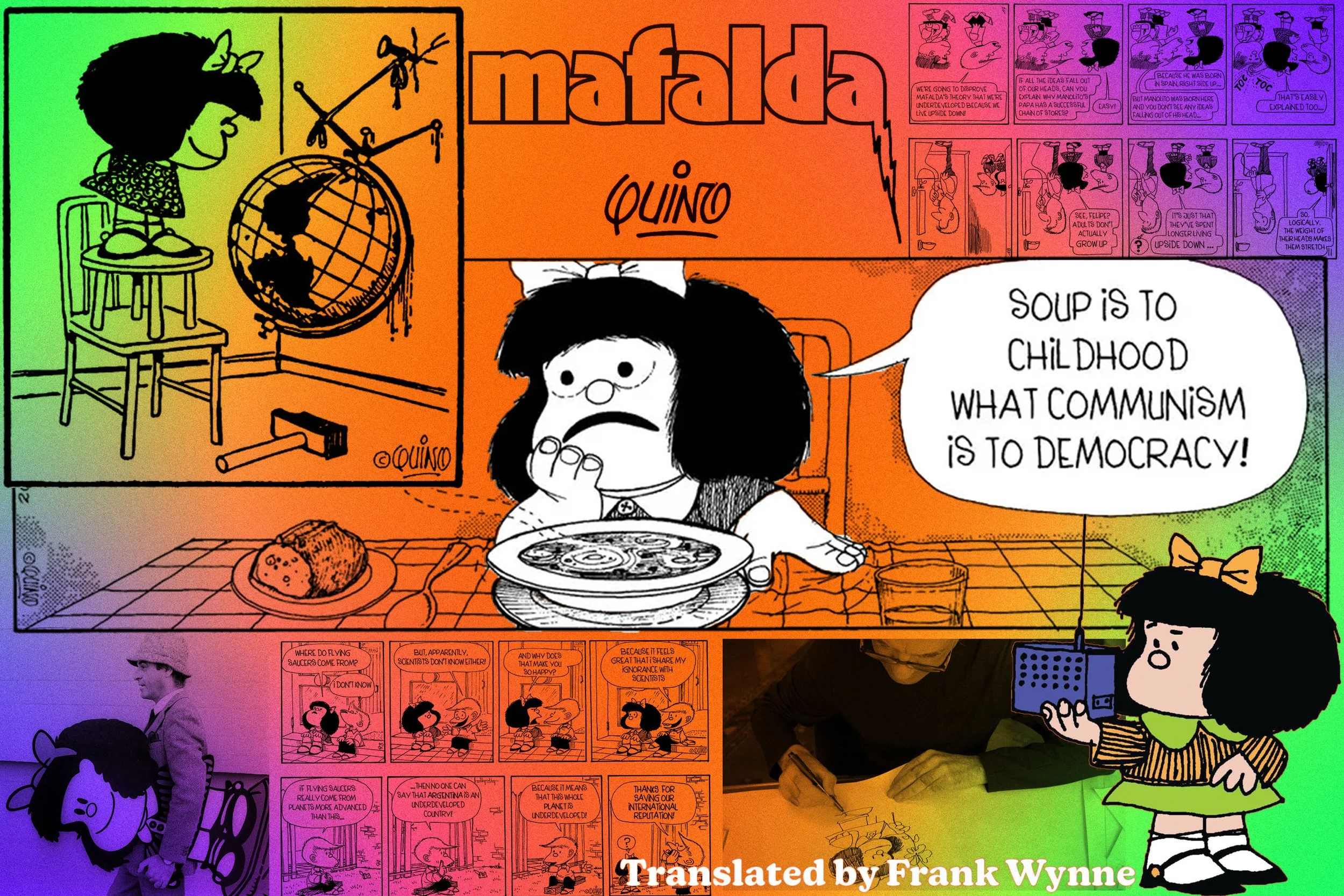

A six-year-old girl with a mane of black hair stares at the bowl of soup before her. Steam swirls over a slice of French bread. “Soup is to childhood what communism is to democracy!” she declares.

Welcome to “Mafalda,” the beloved comic strip by the late Argentine cartoonist Quino that’s getting a delayed introduction to English-speaking readers. “Mafalda” offered different rewards to different Spanish-speaking demographics across Latin America since its nine-year run from 1964 to 1973 and extended afterlife. Kids could laugh at the antics of the impish, inquisitive yet innocent title character and her family and friends. Adults could smile at the strip’s subversive political humor, including jabs at the Vietnam War and subtler tweaks at Argentina’s military dictatorship. Now, for the very first time, “Mafalda” is also available to English-speaking readers. Irish translator and writer Frank Wynne has rendered 240 strips into English; they are published as one volume by Elsewhere Editions.

Mafalda’s Elsewhere Editions English edition. Image courtesy of Elsewhere Editions

A capacity crowd recently gathered at a bookstore in New York City to hear two experts discuss “Mafalda.” Álvaro Enrigue, an acclaimed Mexican-American novelist whose novel You Dreamed of Empires was released last year, and Lucas Adams, who heads New York Review Cartoons, a publication of the New York Review of Books.

“I grew up reading translations,” Enrigue said. “Everybody did. Translation is a normal thing, a human activity.” He called it “a very big and complicated thing. If there is the spirit, then it works.”

Now married to an Argentine and a self-described father to a “Mafalda,” he feels this is an opportune time for an English translation, given the current political moment and its resemblance to the Argentina of the 1960s and early ‘70s.

“The monster is rising,” Enrigue said about Mafalda’s era. “It will become worse and worse and worse.”

Enrigue told the crowd at the bookstore how, in childhood, he and his siblings would read the latest Spanish-language book-length compilation of Mafalda.

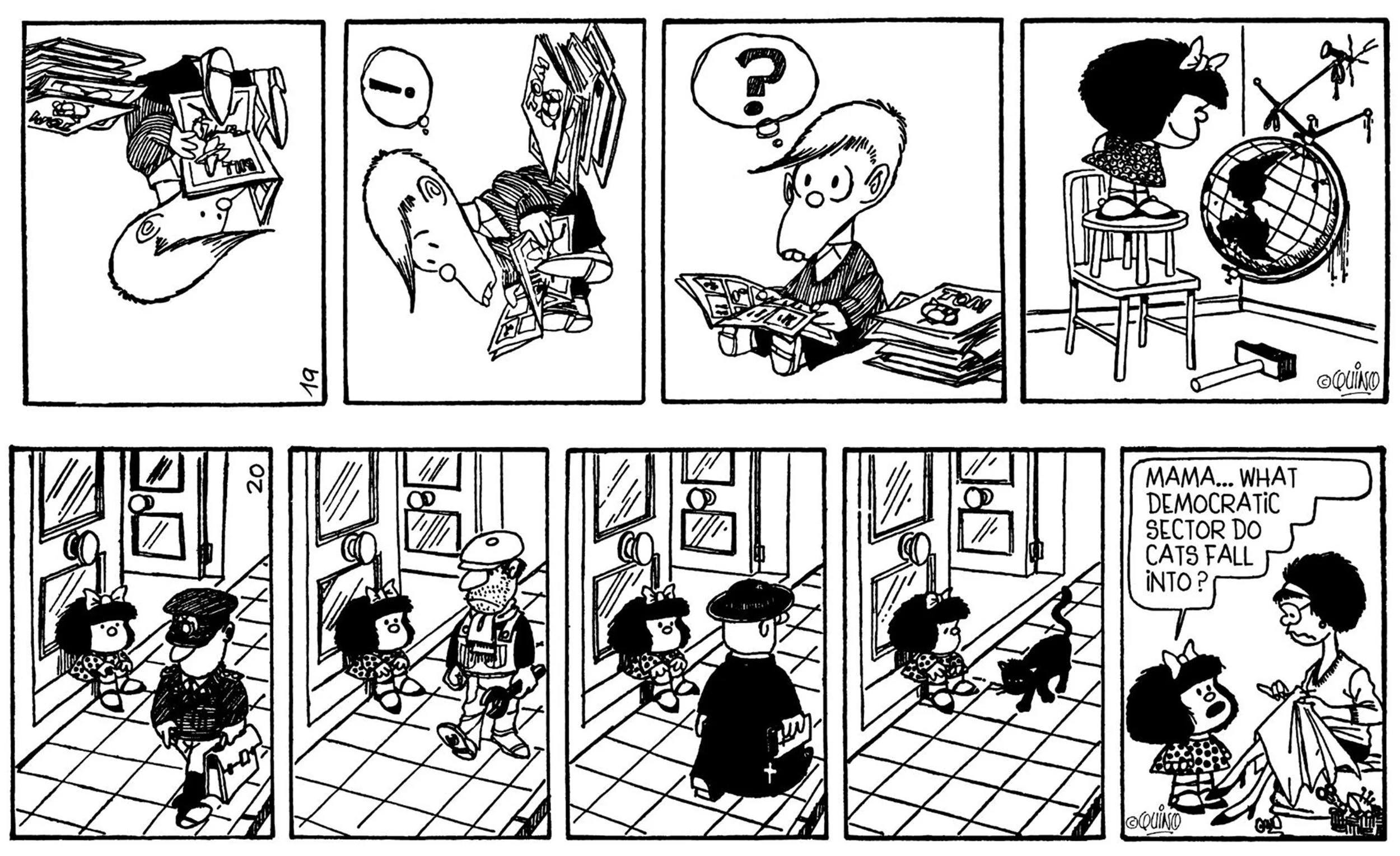

The black-and-white strip focuses on Mafalda as she navigates life in working-class Buenos Aires. Although each strip consists of just a few panels, storylines quickly emerge, whether it’s her wish to be an astronaut or her father’s epic battle with the ants invading their house. Throughout, her distaste for soup is palpable.

“Mafalda” English edition, translated by Frank Wynne, published by Elsewhere Editions. Image courtesy of Elsewhere Editions

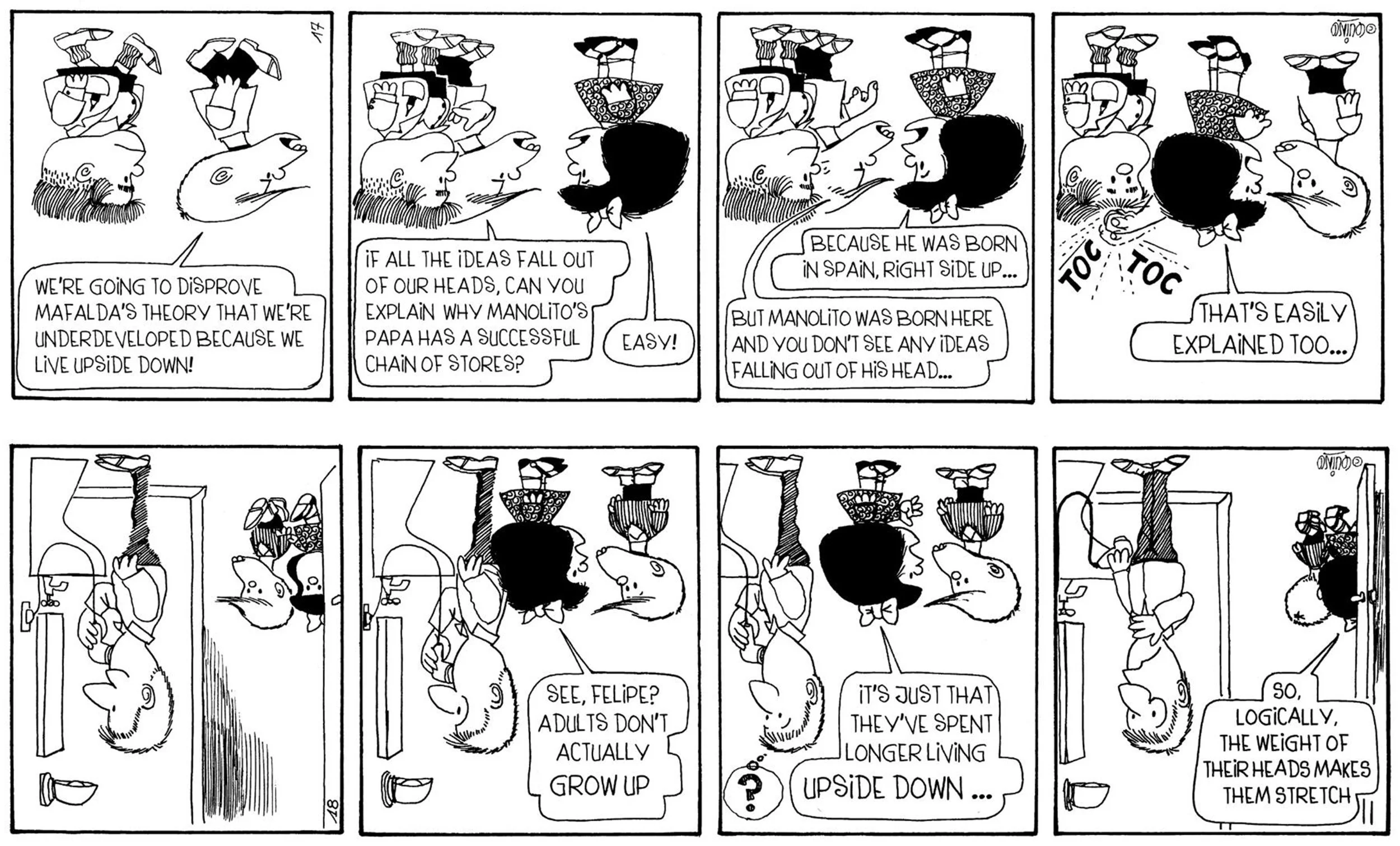

Quino embedded political commentary into seemingly innocuous kiddie comics. This happens when Mafalda’s best friend Felipe takes up chess and tries to teach her the centuries-old strategic game. She repeatedly interrupts with her own interpretations of the rules. In one digression, Mafalda sees a parallel between chess and the class struggle: The king is all-powerful, while the pawns are helpless. Upon realizing this, she exclaims, “And then people are shocked by the rise of communism!”

“Mafalda … seems to be about a group of little kids in Buenos Aires,” said Ulises Gonzales, a lecturer in journalism and media studies at Lehman College in New York City. “In an urban environment, dealing with normal issues like going to school.”

Gonzales is a cartoonist himself, having done comic strips in his homeland of Peru.

He said that Mafalda is actually “about values, democracy, the state of the world, living under a dictatorship.” And, he added, “Most of it was written under an authoritarian regime in Argentina. Somehow, [Quino] got away with it.”

In the compilation, it’s clear that Mafalda and her friends are interested in, and want to understand, the grown-up world. They discuss international topics such as Vietnam, overpopulation, and communism.

“Part of the genius of Quino was that Mafalda never discussed local issues,” Enrigue said. “She was an ultra-globalized girl.”

“Mafalda” English edition, translated by Frank Wynne, published by Elsewhere Editions. Image courtesy of Elsewhere Editions

Yet there were moments when the strip also addressed Argentina’s domestic political situation. When Mafalda sets up an imaginary government headed by herself, she fends off her friends’ military coup attempt. And when a friend’s older brother is drafted into the army, the boys in Mafalda’s group of friends contemplate what it would be like for them to serve, Beatle haircuts and all.

Support the voices of independent journalists.

|

The strip stopped running shortly before the situation worsened in Argentina, with the Ezeiza airport massacre on June 20, 1973, which arguably inaugurated the country’s Dirty War. The Ezeiza Protest and Massacre happened when Argentine anti-communist terrorist snipers attacked a crowd of over two million people who had assembled near the Buenos Aires airport as former President Juan Perón returned from nearly two decades in exile in Spain. Enrigue lamented that an older Mafalda might have become a desaparecida (forcefully “disappeared”) during that troubled time for Argentina.

Yet Enrigue urged audiences to remember that “Mafalda” embodies hope for the future, no matter how hard the grownups make it.

“The world is very depressing,” Enrigue said, yet “Somehow it’s full of tenderness.” This tenderness, he added, “makes you feel optimistic about something you cannot be optimistic about – the world as it is. My wife was saying yesterday, ‘We need Mafalda now, we really need Mafalda now.’ This is a Mafalda moment. Her child wisdom really opens a different kind of window into reality.”

“Mafalda” English edition, translated by Frank Wynne, published by Elsewhere Editions. Image courtesy of Elsewhere Editions

—

Rich Tenorio is a writer and editor whose work has appeared in a variety of media outlets. He is a graduate of Harvard College and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. Tenorio is also a cartoonist. @rbtenorio

Patricia Guadalupe, raised in Puerto Rico, is a bilingual multimedia journalist based in Washington, D.C., and is the co-managing editor of palabra. She has been covering the capital for both English- and Spanish-language media outlets since the mid-1990s and previously worked as a reporter in New York City. She’s been an editor at Hispanic Link News Service, a reporter at WTOP Radio (CBS Washington affiliate), a contributing reporter for CBS Radio network, and has written for NBC News.com and Latino Magazine, among others. She is a graduate of Michigan State University and has a Master’s degree from the Graduate School of Political Management at George Washington University. She is the former president of the Washington, D.C., chapter of NAHJ and is an adjunct professor at American University in the nation’s capital and the Washington semester program of Florida International University. @PatriciagDC