Diary Of A Pandemic: California’s “Coronavirus State Prison”

Inmates' families and activists protest outside of California's San Quentin state prison. Photo courtesy of the San Francisco Bay Area Independent Media Center.

A veteran journalist was helping out by teaching journalism to prisoners. She looked on as thousands of inmates became infected. Dozens have since died, turning San Quentin into a coronavirus hotspot

By Lourdes Cárdenas

As it has ripped through prisons across the country, COVID-19 has claimed inmates’ hopes and voices. In many cases, even their lives.

For more than a year, until the virus engulfed a large population of inmates and guards, I had traveled once a week to teach journalism to Spanish-speaking prisoners inside San Quentin State Prison, California’s notorious lock-up across the bay from San Francisco.

As many as 30 students met with me for two hours in the offices of the San Quentin News, a monthly newspaper produced by inmates and distributed to more than 30 detention facilities across the United States. My students wrote for the San Quentin News, and for Wall City Edición Español, a Spanish-language sister publication.

In class, I would take the inmates through fundamental concepts such as sentence structure and basic Spanish grammar as well as more advanced topics like techniques of reporting, interviewing and writing a story.

A video file by a San Quentin prisoner, shared with a San Francisco Bay Area news station.

Lives in lock-up

It took a while, but as the prisoners grew more comfortable, we shared many vivid discussions about stories on prison life that they considered newsworthy.

Some mentioned the difficulties of accessing proper medical care, especially for the older prisoners. Others discussed the painful process of losing touch with family and friends. But they also discussed positive stories, many related to the rehabilitation and the exhaustive preparation they needed to go before the Board of Parole for an early release.

San Quentin was once considered a very dangerous prison, but that image has changed thanks to numerous reforms and rehabilitation programs.

Today, it has the only on-site college degree-granting program in California's prison system. San Quentin also offers a variety of psychological, educational and vocational programs aimed at helping inmates return to society once their sentences end.

Each day, hundreds of volunteers arrived to donate their time. Inmates recognize and respect the job of volunteers and make sure you can work in safe conditions.

The San Quentin News, in particular, has the support of dozens of advisors and volunteers from the University of California, Berkeley. The Spanish-language journalism I taught was part of that effort.

In the classes I teach at San Francisco State University, the mostly young students have about the same level of education. The San Quentin inmates are a very diverse group in terms of age, schooling and -- in particular -- the crimes they’ve committed and the sentences they’re serving.

Some of the men are spending as little as five years behind bars. Others are “lifers” who will never breathe free air again.

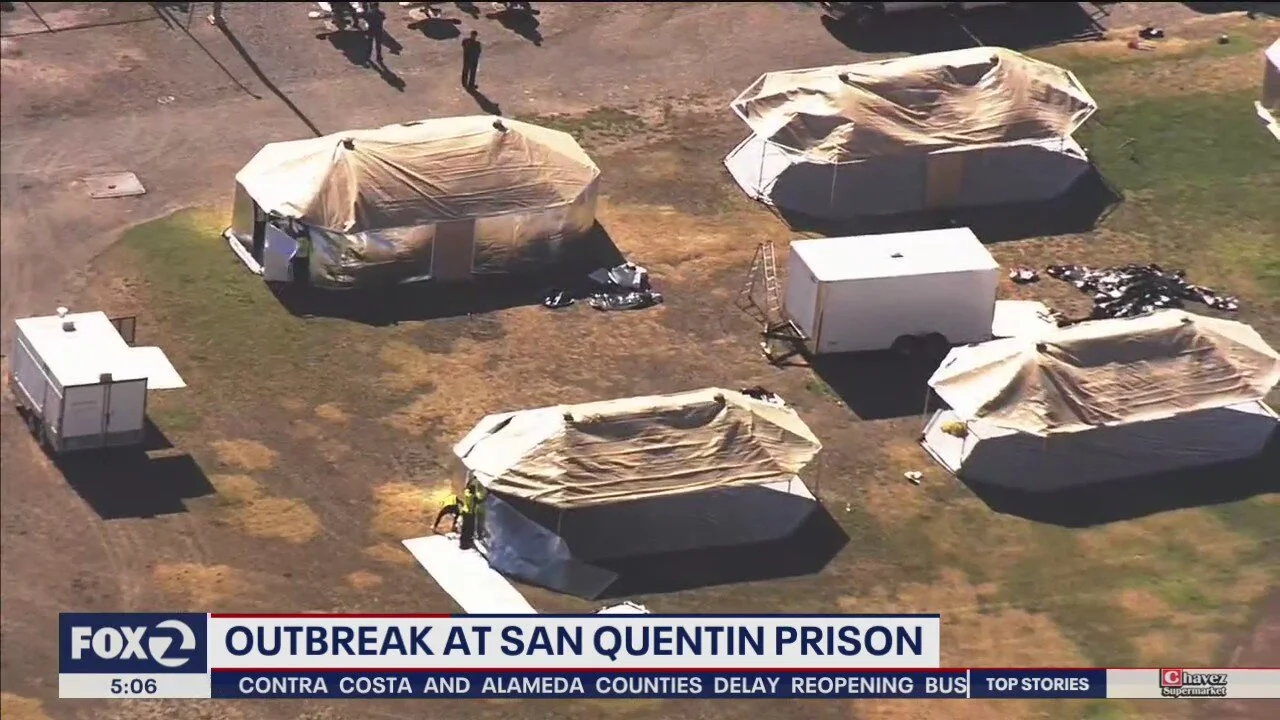

Television news aerial shot of temporary camps set up on the San Quentin state prison grounds, after an outbreak of COVID-19.

An escape for storytellers

I made it a policy not to ask the students about the crimes they had committed, in order to not be biased in my dealings with them. My volunteer work there was to teach them something useful, not to be another judge in their lives.

The inmates’ motivations for learning journalism were different as well. For some, the class offered an escape from the boredom of prison. But for many others, it was a way to acquire skills to prepare themselves for a future in freedom.

The classes also were a window to the outside, which oddly provided the opportunity to view and discuss stories inside the prison walls from a journalistic perspective.

Through journalism, many of my students came to realize that their voices had power and could be heard. The class gave them the opportunity to write about things they were passionate about.

Pedro E. would propose stories related to the achievements of the San Quentin various sports teams. Carlos D. would come with detailed stories on each game of the Earthquakes, the prison’s soccer team. Heriberto A. wrote of his concerns about the lack of Spanish language books at the prison library.

Nearly everyone had interesting story ideas. Most understood that, one way or another, their stories could promote changes in the justice system.

With only a primary school education, Daniel L. would need a ruler in order to write straight on a page, making his handwriting very geometrical. But he would come to class with pages and pages of interviews, relating the stories of men who have been inside for decades, or who have overcome addictions, or who were preparing to be released soon.

Daniel sometimes felt frustrated because, in spite of the long notes he took, he didn’t ask basic questions for a news story, such as when and how something had happened. But he learned fast and would come back prepared to answer all of the questions I had when we sat down to rework the story.

Daniel loved interviewing but he struggled with writing. His goal was to improve it because his dream was to see all the stories that he had collected published someday in a book.

“Writing is one of his therapies,” Daniel’s daughter, Dania Arriola, told me from her home in the northern Mexican city of Monterrey. When a story was published in the Spanish section of the San Quentin News, Daniel would call Dania to let her know.

“He sent me clips of the San Quentin News, where the story was published, and he asked me to check if it was online and then to scan it,” Dania said.

Stop the presses

Then COVID19 struck, changing everything.

Prison officials at first suspended the rehabilitation programs in an attempt to stop the spread of the virus inside San Quentin. Yet soon and paradoxically, some 120 inmates from a heavily infected prison in Southern California were transferred to San Quentin.

The virus spread like wildfire through the cell blocks.

By early August, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation reported the deaths of 22 people at San Quentin. More than 2,000 inmates -- 60% of the population -- and 260 employees had tested positive for the virus, the department reported.

If the entire U.S. public health system was not prepared to deal with such a malignant virus, how would the prison system be different? How would it be possible to reinforce social distancing among people crammed together -- two in every 10 by 4-foot cell, where proper sanitary conditions are all but non-existent?

Chaos ensued. With it came desperate attempts to control the virus’ dissemination.

Inmates were locked down in their cells. Recreation hours were reduced to a minimum. Phone privileges were curtailed. And access to showers was limited to once a week. Boxed lunches replaced regular cafeteria meals. A prison factory was converted to an improvised hospital.

News coming from the prison fed relatives’ concerns for the inmates inside.

A dark outlook

Dania prefers to think that her father’s spirituality, as well as his daily exercise routine, would help him overcome any Covid infection, even though he has a pulmonary problem.

But darker thoughts are constant.

Though she maintains regular contact with her father via phone calls and letters, Dania hasn’t seen him in 14 years because she doesn’t have a United States visa. Her two sisters, who live in Tijuana, last visited Daniel in April 2019.

“What worries me more is that he could die,” Dania told me of her father, who is serving a 32-year sentence. “If he dies, his body probably would go into a mass grave and we won’t be able to claim it.”

This week, Dania was finally able to talk with Daniel, and she learned that he had been infected and was in isolation for an entire month. His symptoms were not serious and he is now recovering.

When the virus forced the San Quentin News to temporarily shut down in March, Editor Juan Espinosa had already finished the layout for the second edition of “Wall City,” the Spanish language magazine produced by inmates.

The prisoner-journalists’ stories remain untold, at least for now.

One of those stories explores how inmates experienced the loss of family members to the virus and how difficult it is to mourn them from prison. Another, written by Daniel, tells of an 86-year-old prisoner set free after forty years, exploring the old man’s process of re-adapting to the outside world.

I expect that authorities will find a way to control the virus and reduce the loss of lives inside the San Quentin. I imagine that Dania, and many others like her, will be able to see or talk with their jailed loved ones again.

But I’m worried about the impact that COVID-19 will have on rehabilitation programs like my journalism classes. I’m afraid the benefits of rehabilitation that San Quentin has won as an institution will be reversed. I fret that the advances many prisoners have attained may be lost to the pandemic.

I’m afraid that hope will vanish.

---

Lourdes Cardenas is an assistant professor at San Francisco State University, where she is developing a Spanish-language journalism program. She has years of experience working for American and Mexican media outlets and is the author of “Marihuana: El Viaje a la Legalización.”